|

|

Beauty is in the details. Click

on the photos to see them in a larger size. Use your browser's

"Back" button to return. |

|

|

|

|

Introduction |

|

So

you inherited Grandma's old hand-me-down furniture or maybe you

found that ideal piece at the flea market, but it is showing a lot

of signs of wear and tear from years of abuse then sitting in a

storage shed for 20 years. Restoring an old piece of furniture

is not as easy as some of the do-it-yourself television shows may

lead you to believe. Sure, if you want to slap a coat of paint

on it and deem it "shabby sheik" then go for it. However,

bringing back the beauty of the original stained wood and fixing the

broken bits correctly and inconspicuously requires time, patience,

and experience. Many folks might be up for the task on the

first day, then quickly lose interest once they understand the

commitment required. So

you inherited Grandma's old hand-me-down furniture or maybe you

found that ideal piece at the flea market, but it is showing a lot

of signs of wear and tear from years of abuse then sitting in a

storage shed for 20 years. Restoring an old piece of furniture

is not as easy as some of the do-it-yourself television shows may

lead you to believe. Sure, if you want to slap a coat of paint

on it and deem it "shabby sheik" then go for it. However,

bringing back the beauty of the original stained wood and fixing the

broken bits correctly and inconspicuously requires time, patience,

and experience. Many folks might be up for the task on the

first day, then quickly lose interest once they understand the

commitment required.

Let me throw this out there right up front: You will NOT save money

by having a piece of furniture restored. You will certainly be

able to buy a similar piece of quality furniture for less.

Restoration is very time consuming, and time is money. Save

restoration for those items which have particular sentimental value

like that table Uncle Frank made himself that everyone sat around for

Thanksgiving dinner. Perhaps that antique piano evokes

pleasant childhood memories of sitting there with Grandma eating

homemade chocolate chip cookies and singing songs. Another

reason to favor restoration is that sometimes certain woods are no

longer available so a comparable replacement is not an option.

Some people believe that older furniture was made better than it is

made today. That is not always the case. Once I get

inside something and start disassembling it, I frequently find that

those old fabricators could be just as lazy as those you can find

presently. Tools and machining processes have evolved to be

much more precise and accurate. This can be considered either

good or bad. Some label those idiosyncrasies as "character",

but when things fit together better, they usually last longer.

Following is a brief tour through the restoration process and

everything involved. This features Grandma's piano mentioned

above. So before you attack that restoration project you have

collecting dust in the back of your garage, you can see if you

really are up for the challenge. You may also acquire insight into

what it takes to properly restore a piece, and perhaps you may gain

some appreciation for the artistry, skill, time, patience, and

ultimately the cost which goes into such a project. |

|

|

|

Evaluate the Existing Conditions |

|

|

The first thing you have to do is see what you're working with.

My first inclination is to always do the least amount possible, not

because I'm lazy, but as an economic courtesy to the person who will

be paying the bill. This project received a cursory

examination at the client's storage shed, a more detailed look in my

garage, then an additional report after I took some things apart to

look under the hood.

It was pretty obvious that this would not be a quick and dirty job

where I could simply refinish a couple pieces of wood and be done

with it. Here is a listing of some of the things I found:

● All of the exposed wood was scratched up.

● Some areas (especially at the lower corners) had the wood veneer

chipped and broken off.

● The front legs were literally ripped off causing considerable

damage.

● One front pull knob was missing, and some other screws were

missing.

● The stool was pretty beat up.

● The piano harp and hammer mechanisms still appeared to be in good

working order (although I'm not a piano tech).

If this were a quick and dirty, minimally invasive approach, I could

have given a fixed price to make the minor repairs. Since this

would be a complete overhaul, we agreed to do this on a time and

materials basis. Some people cringe at that because they were

probably screwed over at one time by a dishonest person.

Truthfully, I don't do woodworking to pay the bills; I have a day

job already. I do woodworking for fun and to see people smile

when I'm done, but I still need to make a little something to cover the cost of

my tools. I can provide a ballpark estimate, but on a project

like this, you simply don't know what you're dealing with until you

start dealing with it. I provided weekly email updates with

photos and a running cost sheet so the client could see where the

money is going and how fast. The client could stop me at any

time, and I didn't require progress payments. There was only

one payment when the whole job was

done. |

|

|

|

Disassemble Everything |

|

You

can not strip and sand all the wood parts while they're all

screwed together. Stripping works better when the item is laid

flat, and you just have too many tight corners to try to get into.

If the piece comes apart, take it apart. With a larger project

like this, photo document everything, make a list of the order

things came apart, and bag/label the screws for each component. You

can not strip and sand all the wood parts while they're all

screwed together. Stripping works better when the item is laid

flat, and you just have too many tight corners to try to get into.

If the piece comes apart, take it apart. With a larger project

like this, photo document everything, make a list of the order

things came apart, and bag/label the screws for each component.

|

On

this piano, several things came apart in sub-assemblies. The

keyboard, for instance, slid out easily, but then that removed

"tray" came apart in about a dozen more pieces plus the 88 keys.

Label the individual parts on the hidden side or on a piece of tape

so you know where everything goes back in. On

this piano, several things came apart in sub-assemblies. The

keyboard, for instance, slid out easily, but then that removed

"tray" came apart in about a dozen more pieces plus the 88 keys.

Label the individual parts on the hidden side or on a piece of tape

so you know where everything goes back in.

Keep everything organized! This piano came apart in 123 pieces

not counting all the screws and hinges. Lay it all out on the

floor so you don't loose anything and you can see what you're up

against - if not just to annoy the wife. You see, that piano

didn't look like such a big project sitting in the shed. It's

a little different story when you see it like this. |

|

|

|

Strip the Wood |

|

|

|

Stripping finish is not particularly difficult; "tedious" is

probably a better word. Fortunately this piano had more flat

pieces than ones with contours or carving. If you do this

yourself and you're standing at Home Depot looking at the cheap can

of paint stripper versus the expensive can, which do you think you

should buy? Fork up the extra $10 for the expensive can.

It will be the consistency of jelly so it will stick, and it will do

its thing in 15 minutes instead of 45. You simply brush it on

with a cheap chip brush, let it sit for 15-20 minutes, scrape it

off, and sand it.

Don't go expensive on the brush, it'll get dipped into toxic

chemicals. You can wash out the chip brush and use it until it

falls apart Do not use a foam brush; those toxic chemicals

will disintegrate it immediately. I don't use gloves when

doing this, but you have to be aware that if your skin starts

burning, you need to wash it off. Scrape the goo off with a

cheap plastic scraper (plastic doesn't scratch the wood easily) and

a lot of paper towels. Stripping will only remove the clear

top coats from the wood like polyurethane or varnish. Follow

that up with 150 grit in a random orbit sander to sand off the

existing stain, then with 220 grit to smooth it up to accept the new

finish.

After stripping the first few pieces, I found that the wood

underneath was a beautiful, colorful walnut. When furniture is

mass produced, the factory will usually opt for homogenous colors and

sacrifice any cool grain patterns. They do what is called

"toning" where they spray the color onto the surface of the wood.

It's kind of like spray painting, but you can still pick up on some

of the grain underneath. After showing my client the

difference between simply oiling the wood (to bring out the grain)

and toning, she went with oiling. This will really pop the

color and grain patterns out, but there will be some pieces which

will not land in at exactly the same color. |

|

|

|

Clean and Buff Everything Else |

|

|

Since

there is a lag between applying the stripper and scraping it

off, there's time to do other things while the stripper is curing.

Don't just sit there and watch the paint dry. Now that you've

got the entire piano disassembled, this would be the best time to

give everything the once over. Since

there is a lag between applying the stripper and scraping it

off, there's time to do other things while the stripper is curing.

Don't just sit there and watch the paint dry. Now that you've

got the entire piano disassembled, this would be the best time to

give everything the once over.

Those tarnished hinges can use some attention. Start with 200

grit sand paper to get the bulk of the corrosion off. Don't

get too aggressive as things might be brass plated and you

don't want to sand off the plating. For stubborn gunk, break

out your Dremel tool with an appropriate attachment. You can

then switch to brass polish after that for those more visible

accessories.

|

|

The

client told me I could just throw the old wheels out since they

didn't work anymore. After examination, I found that at some

point someone rolled over a sheet of plastic and completely

clogged up the bearings. After 15 minutes with a small

needle-nose pliers and a dental pick, the wheels worked again.

Some degreaser (like Simple Green) will break down the oily stuff.

Then follow that up with sanding, Dremeling, and polishing. Be

mindful when you have that inkling to just throw out that old part.

Where can you find a small, solid metal caster to hold a 400 pound

piano these days? The

client told me I could just throw the old wheels out since they

didn't work anymore. After examination, I found that at some

point someone rolled over a sheet of plastic and completely

clogged up the bearings. After 15 minutes with a small

needle-nose pliers and a dental pick, the wheels worked again.

Some degreaser (like Simple Green) will break down the oily stuff.

Then follow that up with sanding, Dremeling, and polishing. Be

mindful when you have that inkling to just throw out that old part.

Where can you find a small, solid metal caster to hold a 400 pound

piano these days? |

|

The

keyboard tray was one big dust bunny underneath - along with a few

spider nests. There are 88 keys on a piano, and I became

intimately familiar with every one of these. Before you take

them off, number the keys as they are all unique. I gathered

them up in small sets and thoroughly cleaned each individual key

with mineral spirits. Then I vacuumed the tray carefully so I

didn't suck up those felt pads. The

keyboard tray was one big dust bunny underneath - along with a few

spider nests. There are 88 keys on a piano, and I became

intimately familiar with every one of these. Before you take

them off, number the keys as they are all unique. I gathered

them up in small sets and thoroughly cleaned each individual key

with mineral spirits. Then I vacuumed the tray carefully so I

didn't suck up those felt pads.

|

|

Yes, even take a wire brush to the old screws to knock off any

rust. Again, resist the temptation to replace the screws.

Old screws have slightly different diameters and their thread pitch

is different. If you run in a new screw, you might strip the

wood in that old screw hole. Also, there were over a hundred

screws on this project. Do you really want to catalog every

screw so you can buy suitable replacements? Replace the

original screws only when needed or where you messed up those stupid slotted

heads taking them out. |

|

|

|

Patch the Wood |

|

|

You'll want to do any patching as sparingly as possible. Even

though the patch should be less noticeable than broken or chipped

wood, you don't want the thing looking like a quilt either.

Keeping the existing wood in place is usually the better way to go.

Some woods are simply not available any more like Cuban mahogany,

old growth fir, or in this case a vibrant variety of walnut.

However, if a piece of wood is badly beaten up, you might have to

replace the entire piece with a new one and call it a day.

Here's a description for what's involved with patching a broken

area. |

|

|

Chipped veneer is a prime candidate for a patch. You could

never color or stain that and make it look acceptable. First you need

to cordon off the area with some thin material like MDF stuck down

with double-stick (carpet) tape. Then you route out the area

about 1/4" deep. Notice that the sides are nice and square so

you can easily cut a piece of wood to fit back in there. |

|

|

Clean up the area with a chisel and

sandpaper. Find a piece of wood which best matches the color

and grain of the area. In this case I used walnut. It

was a pretty close match to the variety of walnut originally used.

Once the piece receives the finish, it will just about be invisible.

Size the piece to match the void, glue it up, and tape it in to dry.

In about an hour, remove the tape and sand everything smooth and

flush. Then repeat the procedure for all the areas needing

some love. |

|

|

|

Fix the Major Stuff |

|

As

I mentioned earlier, the front legs of this piano were completely

ripped out. This would have been extremely difficult to

accomplish unless the person was particularly motivated. The

tray under the keyboard was a 1 1/4" thick piece of lumber.

The top of the leg had a 3/8" diameter threaded stud which screwed

into an insert nut on the other side. The perpetrator would

have had to pull the nut through the piece of wood. As you can

see, he got the leg off and took a good sized chunk of lumber along

with it. Fortunately, the client still had the legs so those

wouldn't have to be recreated. But the damage was done and

needed to be repaired. As

I mentioned earlier, the front legs of this piano were completely

ripped out. This would have been extremely difficult to

accomplish unless the person was particularly motivated. The

tray under the keyboard was a 1 1/4" thick piece of lumber.

The top of the leg had a 3/8" diameter threaded stud which screwed

into an insert nut on the other side. The perpetrator would

have had to pull the nut through the piece of wood. As you can

see, he got the leg off and took a good sized chunk of lumber along

with it. Fortunately, the client still had the legs so those

wouldn't have to be recreated. But the damage was done and

needed to be repaired. |

The

offending area was carefully routed away. I left a ledge

around the hole so I could get a little more surface area on which

to apply glue. I cut a piece of birch to fit the hole

perfectly, glued it, and clamped it home. Birch is a very hard

wood; this leg won't be going anywhere. Once the glue dried, I

sanded everything up smooth and flush, then repeated the process for the other

leg. The

offending area was carefully routed away. I left a ledge

around the hole so I could get a little more surface area on which

to apply glue. I cut a piece of birch to fit the hole

perfectly, glued it, and clamped it home. Birch is a very hard

wood; this leg won't be going anywhere. Once the glue dried, I

sanded everything up smooth and flush, then repeated the process for the other

leg.

|

The

holes for the legs' threaded studs were located and drilled through.

A shallow recess on top will house the threaded insert nut.

The patching is only visible from below. No one sill see it

unless someone sticks their head down there ... and I guarantee

there wouldn't be much piano playing going on. The

holes for the legs' threaded studs were located and drilled through.

A shallow recess on top will house the threaded insert nut.

The patching is only visible from below. No one sill see it

unless someone sticks their head down there ... and I guarantee

there wouldn't be much piano playing going on. |

|

|

|

Apply the Finish |

|

|

After

everything was sanded smooth, I

applied one coat of linseed oil which really brought out the beauty

of the wood. It darkens it up and really pops that grain.

I followed that up with three coats of semi-gloss polyurethane

lightly sanding between the second and third coats.

Polyurethane is tougher than lacquer, but it takes a day to dry.

Then I applied some paste wax and buffed it smooth which lends a

little luster and gives it a nice feel to the touch - it's hard to

describe - it just feels like new. After

everything was sanded smooth, I

applied one coat of linseed oil which really brought out the beauty

of the wood. It darkens it up and really pops that grain.

I followed that up with three coats of semi-gloss polyurethane

lightly sanding between the second and third coats.

Polyurethane is tougher than lacquer, but it takes a day to dry.

Then I applied some paste wax and buffed it smooth which lends a

little luster and gives it a nice feel to the touch - it's hard to

describe - it just feels like new.

The interior of the existing bench was painted so I sanded and

sprayed on a few fresh coats of paint. I covered every detail. |

|

|

|

Put It Back Together |

|

Hopefully

you took good notes and kept all your screws organized. If so,

reassembly is a snap. Take your time so you don't scratch that

freshly finished wood. Now let's take a look at the completed

product. Hopefully

you took good notes and kept all your screws organized. If so,

reassembly is a snap. Take your time so you don't scratch that

freshly finished wood. Now let's take a look at the completed

product.

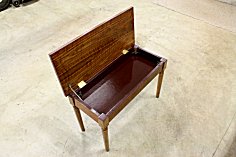

First off you notice that the finish is beautiful, better than the

original (even when it was new). Look at the wood grain on

that stool. Wow! Go ahead, click on the thumbnails for

the larger photos.

|

There

are three wood patches in the first photo to the right. Two

blend in pretty good; I'll concede on the third, but these are much

less noticeable than chipped off bare wood. There

are three wood patches in the first photo to the right. Two

blend in pretty good; I'll concede on the third, but these are much

less noticeable than chipped off bare wood.

Everything was refinished including the music stand.

Everything was cleaned and buffed like those music stand mounting

pivots.

|

Every

key was hand cleaned. One pull knob on the key cover was

missing. I provided two new ones which were a close match.

Even the issues you can't readily see were addressed. I added a spacer

to the top assembly so the screw wasn't bending that little metal

"L" bracket. I added new rubber bumpers so the top doesn't

slam down. The details! Every

key was hand cleaned. One pull knob on the key cover was

missing. I provided two new ones which were a close match.

Even the issues you can't readily see were addressed. I added a spacer

to the top assembly so the screw wasn't bending that little metal

"L" bracket. I added new rubber bumpers so the top doesn't

slam down. The details! |

Even

the stool was refinished. Look at the gleam on those buffed

out hinges. This looks like it just came in brand new from the

showroom. Even

the stool was refinished. Look at the gleam on those buffed

out hinges. This looks like it just came in brand new from the

showroom.

Many people want to refinish that old antique, but few are willing

to put in the time to do it right. Did you think this was

going to be a quick weekend job while throwing back a few beers?

This restoration took me 48 hours. It was a labor of love and

I took the time to respect each individual component. That

love shows in the finished product. Now it will be ready to

host my client (and any new grand daughters down the line) to create

new memories of fresh baked cookies and Christmas carols. |