| Brian's Guitar from Conception to Birth or How to Build a Guitar in 62 Easy Steps! |

| Preparation |

| You wonít want to

attempt to do your own build unless you have some knowledge of how

to use woodworking tools. This project will require a high level of

skill, patience, and experience in woodworking. If youíre missing

any of those traits, your build will probably not come out as

professional looking as you might expect. I donít want to discourage

anyone, but this will cost a good sum of money and a large

investment of time. If this is your first guitar build, you

obviously wonít know what youíre doing. This dialogue will recount

my experience on this particular guitar. Your experience may vary

and difficult situations might arise so you will have to fall back

on your woodworking experience to fill in the gaps. I canít teach

you woodworking here or show you how to use every tool, but I can

outline the steps in making a guitar and throw in a few tips here

and there. If youíre planning on building a guitar to save some money, youíd be in it for the wrong reason. The tab for this build was over $1,000 in materials alone (see the Specifications listing in Appendix A). This does not count the cost of the tools used. Building your own guitar is a mark of pride in your craftsmanship and a sense of accomplishment. You can create your own designs and include the components and details you want. You donít have to settle for whatís hanging up in the store. Before you start whacking away at a pile of wood, youíll want to get yourself a little prepared and build up a some confidence. I started off by reading books and scouring the internet to gain as much background knowledge as I could. Through that research, I developed a checklist of everything Brian would have to consider when writing the specs for his new instrument, and I put him to work (see the Design Considerations checklist in Appendix B). While Brian was busy researching and buying parts for his dream machine, I got to work on sorting out the details of the design. You need to make ALL of your choices up front (notice the bold and all caps). You have to be VERY thoroughly prepared because once you start cutting and gluing up wood, thereís no going back. It is also imperative that you purchase everything before you start. You need to have all the parts in your hand so you can measure all the components and prepare an accurate design based on precise and actual dimensions. Little things like the height of your bridge or the width of your nut will dramatically effect the way the guitar is put together. Avoid the temptation to just start cutting wood until youíve developed a full scale drawing of the guitar.  Brian

loves the Paul Reed Smith body style, so we went to Guitar Center

and traced one. Please ask permission first and donít use indelible

ink which might end up on the guitar or youíll end up buying that

guitar instead of making one. I took the tracing to the drawing

board, laid out a centerline, and plotted all the points around the

body. Fortunately I have AutoCAD at work so I could transfer

everything into the computer and work with more precision than doing

everything with a pencil and a ruler. I input the dimensions into

the computer and refined things up a bit. Though complete

plagiarization is alright here, you should tweak some of the details

to make the design your own (otherwise just buy the PRS). I tweaked

the proportions a little and played around with the headstock design

and inlay patterns. Brian wanted to personalize the electronics

package. Brian

loves the Paul Reed Smith body style, so we went to Guitar Center

and traced one. Please ask permission first and donít use indelible

ink which might end up on the guitar or youíll end up buying that

guitar instead of making one. I took the tracing to the drawing

board, laid out a centerline, and plotted all the points around the

body. Fortunately I have AutoCAD at work so I could transfer

everything into the computer and work with more precision than doing

everything with a pencil and a ruler. I input the dimensions into

the computer and refined things up a bit. Though complete

plagiarization is alright here, you should tweak some of the details

to make the design your own (otherwise just buy the PRS). I tweaked

the proportions a little and played around with the headstock design

and inlay patterns. Brian wanted to personalize the electronics

package.While I was busy on the design and layout, Brian was buying stuff like a kid in a candy store. There are a few local sources for things, but the internet proved to be the best resource for opening up the most options for all the products. As Brian received the goods he passed them along to me. I in turn got out my (metric) ruler and digital calipers to document all the components and draw them up on the computer. The details of the design will start to come together as you let the individual components steer you.  To

lay out the neck, you need the nut width on one end and the bridge

width on the other. You need to know your scale length and fret

spacing (there are plenty of charts for this on the internet). The

bridge height will dictate how much your neck tilts back from the

body. The dimensions of the tuning machines will place some

restrictions on how you lay them out on the headstock. The depth of

your electronics will let you know how thick to make the body and

how large the control cavity has to be. You definitely donít want to

find out that you donít have enough room inside after youíve got the

guitar completely finished. You get the drift. You want to avoid

being surprised after mis-cutting that $100 piece of quilted maple.

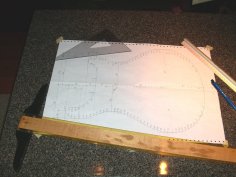

The photo shows a full scale drawing of Brainís guitar and a section

through it. Both are critical to have worked out before you start

(see the Design Diagrams in Appendix C). To

lay out the neck, you need the nut width on one end and the bridge

width on the other. You need to know your scale length and fret

spacing (there are plenty of charts for this on the internet). The

bridge height will dictate how much your neck tilts back from the

body. The dimensions of the tuning machines will place some

restrictions on how you lay them out on the headstock. The depth of

your electronics will let you know how thick to make the body and

how large the control cavity has to be. You definitely donít want to

find out that you donít have enough room inside after youíve got the

guitar completely finished. You get the drift. You want to avoid

being surprised after mis-cutting that $100 piece of quilted maple.

The photo shows a full scale drawing of Brainís guitar and a section

through it. Both are critical to have worked out before you start

(see the Design Diagrams in Appendix C).We got excited to jump into things so we satisfied that urge by buying some wood (December 14, 2007). I took a few rough dimensions off my old guitar so I was sure we would get enough. Wood choice is mostly dictated by personal preference, but there is one major rule to follow: select hard woods which resist warping. Brian decided on the following (from top to bottom in the photo):  ●

Headstock Veneer: Lacewood. While in the wood store, Brian just

thought this looked cool so we found a use for it. Itís only about

3mm thick and it will simply be used to dress up the headstock and a

few other areas. Oh, get used to the millimeter thing. It is far

easier to work in metric for this precise work than in imperial

units. Where do you mark 1.693"? Or what is half of 3 19/64"? If you

always use millimeters, you will always know where to mark 43mm or

what half of 84mm is. Donít worry, youíll get used to it and

appreciate it after a while. But most importantly, you will make

less measuring and calculating errors. ●

Headstock Veneer: Lacewood. While in the wood store, Brian just

thought this looked cool so we found a use for it. Itís only about

3mm thick and it will simply be used to dress up the headstock and a

few other areas. Oh, get used to the millimeter thing. It is far

easier to work in metric for this precise work than in imperial

units. Where do you mark 1.693"? Or what is half of 3 19/64"? If you

always use millimeters, you will always know where to mark 43mm or

what half of 84mm is. Donít worry, youíll get used to it and

appreciate it after a while. But most importantly, you will make

less measuring and calculating errors.● Body Back: Mahogany. A stable and lighter wood that cuts like butter. ● Neck: Hard Maple. Look for straight grain which is less likely to warp. ● Fretboard: Macassar Ebony. This is a very hard wood which is also very dark so you wonít see your finger grunge as much. This comes in jet black, but we selected a piece with some attractive grain pattern in it for a little visual interest. ● Body Front: Quilted maple. This is where Brian splurged, but this is also the part everyone sees first. We got a piece thick enough where we could cut it in half and bookmatch the leaves. This piece was purchased on Ebay while all the other wood was purchased at The Wood & Shop, a local wood supply store. We had to buy a little more wood than we actually would use since the wood stores usually wonít slice things down for you. Use the leftover pieces to practice cutting or finishing on or save them for your next guitar! A note on safety. Youíll see that all of the photos of me operating a table saw show that Iíve removed the blade guard and splitter. Some folks will tell you itís for clarity of the photograph. I wonít tell you that; I never use them since they get in the way more often than not. But I am also fully aware that my finger might get in the way, too. I wonít preach to you on your own safety; thatís your own responsibility. One simple rule in woodworking is that if you donít feel comfortable doing it, donít do it. But you might not be experienced enough (or smart enough) to know when something is unsafe. If thatís the case, again, donít do it. Find someone who can help you through the tough bits. It would really kind of suck to build this great guitar and not have any fingers left to play it. Even though this will be a one-off guitar, making some jigs and templates will greatly increase the accuracy of your build, and you will be able to use some of them on your future builds if you aim on doing another. A template is always better and safer to use than free-hand routing. A router bit spins at over 20,000 rpmís. If it grabs the wood unexpectedly, it will take you for a ride in the best case; it will easily take a finger off in the worst case. With a table saw you might have something to sew back on. Planting a router into your hand is akin to sticking your digits in a blender. Templates will help you keep control of the tool and are essential for making precise, straight, and repeatable cuts. You will notice that I made many jigs and templates to help me with this build. You can make them as basic or as complete and full-featured as you see fit. Make them as you need them and design a few of your own. I donít include a lot of dimensions here as many of them will be tailored to this particular build. Use the concepts and make the designs your own with available materials. The goal for any jig and template is precision, repeatability, and safety. |